FBI (United States Federal Bureau of Investigation)

█ ADRIENNE WILMOTH LERNER

The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the nation's primary federal investigative service. The mission of the FBI is to uphold and enforce federal criminal laws, aid international, state, and local police and investigative services when appropriate, and to protect the United States against terrorism and threats to national interests.

The FBI employs nearly 30,000 men and women, including 12,000 special agents. The organization, headquartered in Washington, D.C., is field-oriented, maintaining a network of 56 domestic field offices, 45 foreign posts, and 400 satellite offices (resident agencies). The agency relies on both foreign and domestic intelligence information, to aid its anti-terror operations. As a law enforcement authority, the FBI only has jurisdiction in interstate, or federal, crimes.

Origins and Formation of the FBI

In the nineteenth century, municipal and state governments shouldered the responsibility of law enforcement. State legislatures defined crimes, and criminals were prosecuted in local courts. The development of railroads and automobiles, coupled with advancements in communication technology, introduced a new type of crime that contemporary legal and law enforcement system was unequipped to handle. Criminals were able to evade the law by fleeing over state lines. To combat the growing trend of interstate crime, President Theodore Roosevelt proposed the creation of a federal investigative and law enforcement agency.

In 1908, Roosevelt and his attorney general, Charles Bonaparte, created a force of Special Agents within the Department of Justice. They sought the expertise of accountants, lawyers, Secret Service agents, and detectives to staff the ranks of the new investigative service. The new recruits reported for examination and training on July 26, 1908. This first corps of federal agents was the forerunner of the modern FBI.

When the federal bureau began operations, there were few federal crimes in the legal statutes. Federal agents investigated railroad scams, banking crimes, labor violations, and antitrust cases. The findings of their investigations, however, were usually disclosed to local or state law enforcement officials and courts for prosecution. In 1910, the federal government passed the Mann Act, expanding the jurisdiction of the investigation bureau by outlawing the transport of women over state lines for the purpose of prostitution. Granting federal agents the right to investigate, arrest, and prosecute persons in violation of the Mann Act solidified the interstate authority of federal investigative services.

The Special Agents force also aided border guards, investigating smuggling cases and immigration violations. At the outbreak of the Mexican revolution, bureau agents conducted limited espionage operations, gathering intelligence for the military and the government.

World War I and the Interwar Years

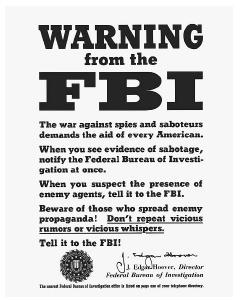

When World War I erupted in Europe, the United States government, under President Woodrow Wilson, proclaimed American neutrality in the conflict. Despite the official declaration of neutrality, the United States increasingly aided Allied nations such as Britain and France with sales of weapons and supplies for the war effort. As a result, rival Germany sent saboteurs and spies into the United States to conduct espionage against United States military instillations and ammunition factories. Several incidents, including an explosion near New York City, at Black Tom Pier, fanned public fear of German spies and saboteurs infiltrating the United States. Federal investigators were charged with investigating acts of terrorism and sabotage, as well as ferreting out potential spies. For this job, Special Agents worked closely with military intelligence, gaining new law enforcement and espionage tradecraft skills.

With the entry of the United States into the European conflict, federal investigators gained jurisdiction over the enforcement of the Espionage, Sabotage, and Selective Service Acts. The bureau investigated alien enemies, and arrested men who dodged conscription.

After World War I ended in 1918, the force of Special Agents became the Bureau of Investigation. The agency gained considerable autonomy from Department of Justice oversight. During the 1920s, federal agents investigated several regional and national crime syndicates. Prohibition, the ban on sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, prompted a rise in the illegal manufacture, trade, and sale of alcohol. Since the Department of the Treasury had jurisdiction over Prohibition violations, federal investigators worked closely with Treasury agents.

The interwar era was also marked by increased gangsterism. Gangsters posed a unique challenge to the Bureau of Investigation's narrow interstate jurisdiction. Many of the most notorious crime bosses were eventually arrested on charges of racketeering, tax evasion, or war profiteering. With no other means available, within their legal bounds, to bring down the resurgence of the often violent and well-armed Ku Klux Klan (KKK), the Bureau of Investigation targeted the leader of the Louisiana Klan for violations of the Mann Act.

The onset of the Great Depression helped escalate crime rates. The sour economy gave rise to increased labor violations, corruption, swindling, and murder. Two events, however, strengthened and expanded the Bureau of Investigation's jurisdiction. The kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932 prompted Congress to pass federal kidnapping statutes. Two years later, Congress passed legislation prohibiting the escape of criminals across state lines, providing for interstate extradition of criminals, and granting federal agents the right to investigate and arrest criminals who fled or operated across state lines. Further reforms of federal law enforcement services permitted agents to carry guns.

The structure of the agency changed dramatically in the 1920s and 1930s. J. Edgar Hoover assumed the directorship of the Bureau of Investigation. Hoover expanded the field office network from nine offices to over 30 offices within ten years. Agency personnel policy changed, requiring new agents to complete a rigorous, centralized training course. Promotions within the organization were secured through merit and consistency of service, not seniority. The agency still sought agent-recruits with training in accountancy and law, but expanded their search to include linguists, mathematicians, physicists, chemists, forensics specialists, and medical practitioners.

Technical advancements also changed agency operations. Basic forensic investigation began to be employed in FBI crime scene investigations. The bureau established a fingerprint identification and index system in 1924. The national index assumed fingerprint records from state and local law enforcement agencies, as well as an older Department of Justice fingerprint registry dating back to 1905. The agency opened its first technical laboratory in 1932. The facility quickly expanded to cover a variety of forensic research, aiding investigators by comparing bullets, guns, tire tracks, watermarks, counterfeiting techniques, handwriting samples, and pathology reports.

World War II and the Interwar Years

In 1935, the special task force of agents who formerly worked to combat Prohibition were separated from the agency, and the organization was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). When war again broke out in Europe, FBI agents performed many of the same duties as they had during World War I. Before the United States entered the war in 1941, the FBI concentrated its efforts on locating, infiltrating, and dismantling political organizations sympathetic to German and Italian Fascism, and Soviet Communism, despite the latter nation's wartime alliance with Britain and France. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, pushed for increased power for the FBI to investigate perceived subversives, even if these people were ordinary American citizens. A 1939 presidential directive, followed by the Smith Act of 1940, outlawed public advocacy of over-throwing the government.

When the United States entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, FBI agents aided national defense efforts by placing trained agents at key military and defense industry sites. Wartime agents received more intense training in counterintelligence measures, and the FBI established special counterintelligence units for covert operations at the government's discretion. FBI agents thwarted German and Japanese attempts at sabotaging national interests, including fuel reserves.

World War II also marked one of the darkest chapters of FBI operations. Despite opposition from FBI director Hoover, government officials declared all Japanese immigrants, and American citizens of Japanese descent, enemy aliens. The Japanese-American population on the West Coast was evicted from their homes and sent to internment camps for the duration of the war. Many lost homes and businesses that they were forced to leave behind. Since internment camps and enemy alien laws fell under federal jurisdiction, the FBI imposed curfews, administered deportations, and arrested those in violation of internment laws.

Conversely, FBI agents were the first federal authority since Reconstruction to enforce desegregation laws. Though segregation remained legal practice during the 1940s, the president appointed the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) to address concerns of African-American workers. FEPC possessed no enforcement authority, but FBI agents arrested several employers found in violation of the FEPC on the grounds of impeding the war effort.

The FBI during the Cold War

The early Cold War years. When World War II ended in August 1945, increasingly hostile relations between the United States and the Soviet Union led to the Cold War, a diplomatic and military standoff that lasted over four decades. In the early Cold War years, the American government, and many members of the public, worried about the presence of Communist organizations and spies within the United States. The discovery of Soviet agents operating within government agencies, and the trial of individuals accused of stealing atomic secrets, and the test detonation of the first Soviet atomic bomb in 1949, fanned public anti-Communist hysteria. While the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) worked to stop the expansion of the Soviet Union abroad, the FBI gained the past-war responsibility of defeating Communist organizations at home.

In the first fifteen years of the Cold War, the FBI investigations contributed to the McCarthy hearings, as well as high-profile spy cases like that of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The FBI gained the authority to conduct background checks on potential government employees, and investigate federal employees suspected of disloyal acts or espionage. The 1946 Atomic Energy Act gave the FBI jurisdiction over the secrecy and protection of atomic secrets. Legislation throughout the 1950s expanded the FBI's role to cover the security of atomic facilities, and defense industry sites.

In more routine law enforcement duties, the FBI continued to pursue interstate and federal criminals. In 1950, the agency published its first "Ten Most Wanted List."

The early 1960s and the Civil Rights Movement. Although the Cold War continued, the anti-Communist hysteria faded away in the late 1950s. FBI investigations of anti-government organizations and "subversive individuals" shifted with the political mood of the 1960s. The decade witnessed the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and ushered in the Civil Rights Movement, both events signaled new duties and an expanded legal jurisdiction for the FBI.

When President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas in 1963, the crime was legally a local homicide. No special legal provisions existed for the investigation of the assassination of a government official or the president. President Lyndon B. Johnson called in FBI agents to investigate the murder, setting the precedent for future legislation that designated assassination as a federal crime, and granted the agency jurisdiction in assassination cases.

The FBI was responsible for federal enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and aiding desegregation efforts by investigating pro-segregation organizations and individuals. The FBI's charge to enforce civil rights legislation often put federal agents in conflict with local law enforcement officials, especially in the South and Midwest. Though the FBI routinely investigated violations of civil rights laws, they did not win the authority to prosecute violators through federal law until after 1966.

The FBI investigated, and helped prosecute criminals, in several high profile civil rights cases. Field agents in Louisiana and Mississippi investigated the murder of three voter registration workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, before turning the case over to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. FBI agents conducted crime scene, forensics, and extended investigations of the assassinations of civil rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr., and Medger Evers. They eventually arrested, aided the prosecution of, and gained convictions for the assassins, although Byron De La Beckwith, who shot Medger Evers, was not found guilty until 1994.

The Vietnam and Watergate era. The United States, in an attempt to stem Soviet influence in Asia, entered the Vietnam War. The war was controversial, with many young people opposing U.S. military intervention in the conflict. The re-institution of the draft further angered anti-war sympathizers. Government officials grew increasingly suspicious of anti-war organizations and the large demonstrations they organized. Though the vast majority of anti-war demonstrators and organizations advocated peaceful protest and civil disobedience, a few militant and extremist groups resorted to acts of violence and sabotage. The actions of these groups prompted the FBI to conduct widespread surveillance of the anti-war movement. Utilizing counterintelligence techniques, the FBI used a myriad of intrusive surveillance, known as "Cointelpro," methods to thwart terrorist action by radicals. However, some criticized the organization of conducting domestic espionage, especially on the peaceful majority of anti-war supporters. Hoover, still director of the FBI, responded by promoting passage of the Omnibus Crime Control Act, which limited the use of wiretaps, listening devices, clandestine photographs, and other surveillance methods. The act defined new operational procedures for FBI agents, and was the first legal compromise between intelligence and privacy interests.

In 1972, public attention shifted from the Vietnam conflict, to the actions of the Nixon administration. On June 17, 1972, five men were arrested while breaking into the Watergate apartment complex that housed the headquarters for the Democratic Party. Subsequent investigations by a special team of federal agents connected the men, most whom were former CIA and FBI agents, to the Office of the President. Despite the implication of a few FBI agents in the extensive cover-up operation that followed the break-in, FBI investigators cooperated with a specially appointed Senate investigatory committee, surrendering all information pertaining to Watergate. The ensuing scandal, known as Watergate, not only forced the resignation of Nixon and most of his administration, but also damaged public faith in the government and its intelligence and security agencies.

The end of the Cold War. A period of Cold War détente in the 1980s allowed the FBI to concentrate on agency reforms and expansion of its domestic intelligence capabilities. In 1982, following a outburst of international terrorism, the director of the FBI, William Webster, made counterintelligence and anti-terrorism operations an agency priority. He established the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, a facility that would conduct sophisticated forensic analysis on crimes. The renewed agency attention to counterintelligence discovered over 30 cases of espionage against the United States government in 1985.

Combating the rise of white-collar financial crimes and the drug trade were other priorities of the FBI during the 1980s. FBI investigations implicated high-ranking government officials in financial fraud and abuse of power scandals, including members of the Congress (ABSCAM), defense industry (ILL WIND), and judiciary (GREYLORD). Federal agents also investigated fraud cases during the savings and loan crisis.

The Rise of Terrorism and the FBI Today

In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. Its formal dissolution on December 25, 1991, marked the end of the Cold War. In the decade that followed, the international political map drastically altered, changing the global balance of power and permitting the rise of new threats to United States national security. In response to the changing international environment, the FBI shifted the priority of its operations. Several key events, including the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center by Islamist, foreign terrorists, and the 1995 bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City by a domestic terrorist, prompted the FBI to restructure its counterintelligence and counter-terrorism operations.

To aid its current operations, the FBI embraced the use of several new technologies in its operations. The advent of personal computers and the Internet aided research and processing of investigation information. Searchable databases store information on suspects, crime statistics, fingerprints, and DNA samples. However, their use also created security risks that necessitated the creation of specialized information systems protection task forces. The agency created Computer Analysis and Response Teams (CART) to aid field investigators with the recovery of data from damaged or sabotaged electronic sources. In 1998, the establishment of the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) permitted the FBI to monitor the dissemination of computer viruses and worms.

Forensic use of DNA radically altered both the legal process and forensic research of FBI investigations. DNA analysis allows specialists to positively identify victims and perpetrators of crimes by comparing particular patterns in individual DNA. FBI forensic specialists created a national DNA databank in 1998 to aid ongoing investigations.

After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, and subsequent anthrax attacks on national post offices and media outlets, the FBI expanded its counterintelligence and counter-terrorism operations to include anti-bioterror task forces. The FBI, working in conjunction for the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), employs agents to aid in the investigation and identification of bioterror agents, and law enforcement in the event of a bioterror attack. FBI analysis and research divisions have compiled massive databases on known biological agents, stockpiles of weapons, and terrorist groups who may possess biological weapons. FBI analysts develop profiles of terrorist groups to better understand their mindsets and possible future actions.

The FBI's focus on the prevention of terrorism failed to thwart the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. However, FBI investigations successfully found and prosecuted the perpetrators of the Oklahoma City bombing and the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center. In its ongoing investigation of the events of September 11, FBI agents have found and arrested several persons suspected of having connections to the al-Qaeda terrorist network and the recent terrorist attacks. The FBI is also designated as the primary agency of enforcement for the Patriot Act.

Although no major FBI operations were assumed into the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the establishment of pending DHS committees to govern intelligence agency cooperation and information sharing will alter the manner in which the FBI relays information to the President and other government officials. Proponents of the DHS hope the agency will streamline communication among intelligence and security agencies. Critics of proposed DHS intelligence reforms charge that agencies, such as the FBI, will lose investigative and operational autonomy. Despite the changing future of the structure of the United States intelligence community, the FBI will undoubtedly play a central role.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Kessler, Ronald. The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002.

ELECTRONIC:

United States Federal Bureau of Investigation. < http://www.fbi.gov > (May 2003).

SEE ALSO

Anthrax, Terrorist Use as a Biological Weapon

Black Tom Explosion

CIA (CSI), Center for the Study of Intelligence

COINTELPRO

Cold War (1945–1950), The Start of the Atomic Age

Cold War (1950–1972)

Cold War (1972–1989): The Collapse of the Soviet Union

Commission on Civil Rights, United States

Counter-Intelligence

Counter-terrorism Policy, United States

Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC), United States National

Justice Department, United States

McCarthyism

Pearl Harbor, Japanese Attack on

Privacy: Legal and Ethical Issues

September 11 Terrorist Attacks on the United States

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: