Spanish-American War

█ ADRIENNE WILMOTH LERNER

In the late nineteenth century, the United States grew in industrial and economic strength. By the 1880s, the nation was one of the most robust in the Western Hemisphere, wielding increasing power in the region despite a stated policy of neutrality. In 1898, diplomatic relations between the United States and Spain began to sour over Spain's domination of Latin America and some parts of the Caribbean. Reports of the brutal rule of Spanish General Valeriano Wyler in Cuba inflamed public opinion in the United States. The convergence of anti-Spanish public opinion and the government's desire to protect American economic interests in Cuba prompted tense diplomatic meetings between Spain and the United States.

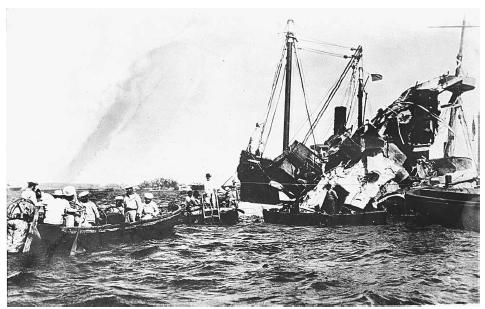

During the negotiations, two events spurred the United States to declare war. A U.S. ship, the USS Maine sank off the coast of Cuba on February 15, 1898. A Navy inquiry board incorrectly declared that a mine fatally wounded the

vessel. 266 Navy seamen and two high-ranking officers perished in the accident. The event consumed newspaper headlines for weeks. Sensationalistic reporting, dubbed "yellow journalism," helped to swell the tide of pro-war sentiment in the United States.

Within weeks of the sinking of the Maine , intelligence operatives intercepted a private letter between the Spanish Ambassador to the United States and a friend in Havana, Cuba. The letter disparaged U.S. President McKinley, and hinted at plans to commit acts of sabotage against American property in Cuba. The letter was published by several newspapers, further agitating public opinion. On April 19, 1898, Congress resolved to end Spanish rule in Cuba.

In the first military action of the war, the United States blockaded Cuban ports on April 22, 1898. The Navy transferred several vessels to neighboring Florida to consolidate the forces available to fight the Spanish in the Caribbean. Naval presence off the Florida coast also facilitated the transfer of information from the battlefront to the government in Washington, D.C.

The Office of Naval Intelligence established sophisticated communications intelligence operations in support of their efforts in Cuba. Martin Hellings, who worked for the International Ocean Telegraph Company, was sent to Key West, Florida, to intercept Spanish messages. Hellings convinced other telegraph operators to copy Spanish diplomatic messages and deliver the copies to him. Within a few days, he operated a sizable communications ring, conducting surveillance on underwater and land-based telegraph cables. Hellings also employed a courier to run special messages between his offices and United States ships in the region.

The theater of war rapidly expanded to include other Spanish strongholds, including the Philippines. Intelligence operations were not initially as well developed in the Pacific as they were in the region around Cuba. Cuba's proximity to the Florida coast aided intelligence and espionage operations. United States military commanders knew little about the Philippines and the Spanish defenses there. To obtain information, the Office of Navy Intelligence and the Army's Military Intelligence Division employed human intelligence. Agents were sent to the remote islands to obtain information about Spanish defenses, military strength, and island terrain. The operation moved swiftly, and within weeks, United States commanders learned that the Spanish were ill-prepared to fight a strong offensive in the Philippines.

On May 1, 1898, the United States Asiatic Squadron, under the command of George Dewey, sailed into Manila Bay and attacked the Spanish. The Spanish fleet was decimated, but the United States sustained no losses. Though the Spanish surrendered the Philippines, the United States fleet remained, and began a campaign to take the island as a United States territory. The ensuing conflict lasted until 1914.

Human intelligence was not limited to operations in the Philippines. The United States employed covert agents in Europe, Cuba, and Canada. These agents aided the war effort by spying on Spanish diplomats abroad and providing intelligence information to dissident groups in Cuba. German-educated Henry Ward traveled to Spain in the guise of a German physician. William Sims, an American attaché in Paris, managed a spy ring throughout the Mediterranean. In Cuba, Andrew Rowan united rebel groups and reported on the location and size of the Spanish fleet. He supervised the trafficking of arms to rebel outfits and helped plan their assaults on Spanish targets. Human intelligence also contributed to counterintelligence efforts. Based on agent reports, the United States Secret Service was able to infiltrate and destroy a Spanish spy ring working in Montreal, Canada.

In June 1898 United States intelligence learned, via telegraph intercepts, that the Spanish fleet planned to attack the U.S. blockade in Cuba and draw ships into a naval battle in the Caribbean. When the Spanish fleet arrived in the region, United States Naval Intelligence tracked them and gave chase. United States commanders hoped to deplete Spanish fuel reserves before engaging them in battle. The United States backed off, and redeployed to aid blockade ships stationed around Havana. The Spanish ships proceeded undetected to the narrow harbor of Santiago, Cuba. When the Spanish commander telegraphed his government to declare his position, U.S. agents working in Florida intercepted the cable. The United States fleet moved to intercept the Spanish at Santiago. The U.S. Navy blockaded the port and immobilized the Spanish fleet. The Spanish attempted to run the blockade on July 3, but the entire fleet of six ships was destroyed.

In the final phase of the war, the United States deployed ground forces to sweep Spanish forces out of Havana and Santiago. The "Rough Riders," the most famous of which was Theodore Roosevelt, worked with rebel groups to take control of the nation's capitol and ferret out remaining Spanish forces in the countryside. The U.S. troops then departed Cuba for Puerto Rico, driving the Spanish from the island.

The war ended with the Spanish surrender on July 17, 1898. The event signaled a new international stance for the United States, as the nation began to acquire territories and dominate the politics of the Western Hemisphere. As a result of the Spanish-American War, or in its immediate wake, the United States gained Guantanamo Bay, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Hawaii.

The Spanish-American War, though a brief conflict, helped to revolutionize United States intelligence organizations and their operations. Before the war, agencies like the Office of Naval Intelligence relied on openly available sources for their information. After the war, personnel were trained in espionage tradecraft, and covert operations became standard intelligence community practice. Congress briefly entertained the idea of establishing a permanent, civilian intelligence corps, but the agency never materialized. Despite the progress made with technological surveillance, espionage tradecraft, and inter-agency cooperation made during the war, the intelligence community was once again allowed to slip into disarray until the eve of World War I.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Musicant, Ivan. Empire by Default: The Spanish-American War and the Dawn of the American Century. Henry Holt, 1998.

O'Toole, G. J. A. The Spanish-American War: An American Epic, 1898. New York: W.W. Norton, 1986.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: