Vietnam War

█ JUDSON KNIGHT

The Vietnam War was a struggle between communist and pro-western forces that lasted from the end of World War II until 1975. The communist Viet Minh, or League for the Independence of Vietnam, sought to gain control of the entire nation from its stronghold in the north. Opposing it were, first, France, and later the United States and United Nations forces, who supported the non-communist forces in southern Vietnam. In 1975, in violation of a 1973 peace treaty negotiated to end United States military involvement in South Vietnam and active war against North Vietnam, North Vietnamese forces and South Vietnamese communist sympathizers seized control of South Vietnam

and reunited the two countries into a single communist country.

American involvement in Vietnam has long been a subject of controversy. The fighting depended, to a greater extent than in any conflict before, on the work of intelligence forces. Most notable among these were various U.S. military intelligence organizations, as well as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Early stages. Led by Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969), the Viet Minh aligned themselves with the Soviets from the 1920s. However, they configured their struggle not in traditional communist terms as a class struggle, but as a war for national independence and unity, and against foreign domination. Vietnam at the time was under French control as part of Indochina, and World War II provided the first opportunity for a Viet Minh uprising against the French, in 1940. France, by then aligned with the Axis under the Vichy government, rapidly suppressed the revolt. Nor did the free French, led by General Charles de Gaulle, welcome the idea of Vietnamese independence.

After the war was over, de Gaulle sent troops to resume control, and fighting broke out between French and Viet Minh forces on December 19, 1946. On May 7, 1954, the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu fell to the Viet Minh after an eight-week siege. Two months later, in July 1954, the French signed the Geneva Accords, by which they formally withdrew from Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords divided the country along the 17th parallel, but this division was to be only temporary, pending elections in 1956. However, in 1955 Ngo Dinh Diem declared the southern portion of the nation the Republic of Vietnam, with a capital at Saigon. In 1956, Diem, with the backing of the United States, refused to allow elections, and fighting resumed. The conflict was now between South Vietnam and the communist republic of North Vietnam, whose capital was Hanoi. Fighting the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) were not only the regular army forces of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), but also Viet Cong, guerrillas from the South who had received training and arms from the North.

American involvement. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had already sent the first U.S. military and civilian advisers to Vietnam in 1955, and four years later, two military advisers became the first American casualties in the conflict. The administration of President John F. Kennedy greatly expanded U.S. commitments to Vietnam, such that by late 1962 the number of military advisers had grown to 11,000. At the same time, Washington's support for the unpopular

Diem had faded, and when American intelligence learned of plans for a coup by his generals, the United States did nothing to stop it. Diem was assassinated on November 1, 1963.

Under President Lyndon B. Johnson, U.S. participation in the Vietnam War reached its zenith. The beginnings of the full-scale commitment came after August 2, 1964, when North Vietnamese gunboats in the Gulf of Tonkin attacked the U.S. destroyer Maddox. Requesting power from Congress to strike back, Johnson received it in the form of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted the president virtual carte blanche to prosecute the war in Vietnam.

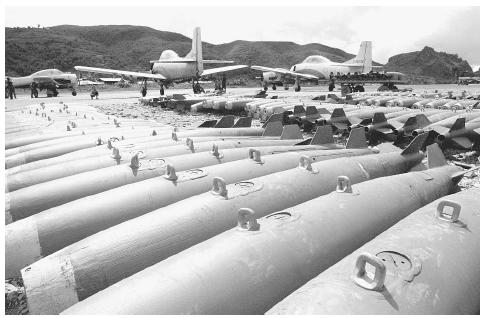

High point of the war. As a result of his strengthened position to wage war, and still enjoying broad support from the American public, Johnson launched a bombing campaign against North Vietnam in late 1964, and again in March 1965, after a Viet Cong attack on a U.S. installation at Pleiku. By June 1965, as the first U.S. ground troops arrived, U.S. troop strength stood at 50,000. By year's end, it would be near 200,000.

General William C. Westmoreland, who had assumed command of U.S. forces in Vietnam in June 1964, maintained that victory required a sufficient commitment of ground troops. Yet by the mid-1960s, the NVA had begun moving into the South via the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and as communist forces began to take more villages and hamlets, they seemed poised for victory. Johnson pledged greater support, but despite growing number of ground troops and intensive bombing of the North in 1967, U.S. victory remained elusive.

The turning point in the U.S. effort came on January 30, 1968, when the NVA and Viet Cong launched a surprise attack during celebrations of the Vietnamese lunar new year, or Tet. The Tet Offensive, though its value as a military victory for the North is questionable, was an enormous psychological victory that convinced Americans that short of annihilation of North Vietnam—an unacceptable geopolitical alternative—they could not win a Korea-like standoff or outright victory in Vietnam. In March 1968, Johnson called for an end to bombing north of the 20th parallel, and announced that he would not seek reelection. Westmoreland, too, was relieved of duty.

Withdrawal (1969–75). The administration of President Richard Nixon in 1969 began withdrawing, and instituted a process of "Vietnamization," or turning control of the war over to the South Vietnamese. In 1970, the most significant military activity took place in Cambodia and Laos, where U.S. B-52 bombers continually pounded the Ho Chi Minh Trail in an effort to cut off supply lines.

Despite the bombing campaign, undertaken in pursuit of Vietnamization and the goal of making the war winnable for the South, the North continued to advance. On January 27, 1973, the United States and North Vietnam signed the Paris Peace Accords, and U.S. military involvement in Vietnam ended.

During the two years that followed, the North Vietnamese gradually advanced on the South. On April 30, 1975, communist forces took control of Saigon as government members and supporters fled. On July 2, 1976, the country was formally united as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and Saigon renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

The intelligence and special operations war. Behind and alongside the military war was an intelligence and special operations war that likewise dated back to World War II. At that time, the United States, through the Organization of Strategic Services (OSS), actually worked closely with Viet Minh operatives, who OSS agents regarded as reliable allies against the Japanese. Friendly relations with the Americans continued after the Japanese surrender, when OSS supported the cause of Vietnamese independence.

This stance infuriated the French, who sought to reestablish control while avoiding common cause with the Viet Minh. They attempted to cultivate or create a number of local groups, among them a Vietnamese mafia-style organization, that would work on their behalf against the Viet Minh. These efforts, not to mention the participation of one of the world's most well-trained special warfare contingents, the Foreign Legion, availed the French little gain.

Special Forces, military intelligence, and CIA. In the first major U.S. commitment to Vietnam, Kennedy brought to bear several powerful weapons that together signified his awareness that Vietnam was not a war like the others America had fought: the newly created Special Forces group, known popularly as the "Green Berets," as well as CIA and a host of military intelligence organizations.

Though Special Forces are known popularly for their prowess in physical combat, their mission in Vietnam from the beginning had a strong psychological warfare component. In May 1961, Kennedy committed 400 of these elite troops to the war in Southeast Asia, and more would follow.

Alongside them, in many cases, were military intelligence personnel, whose ranks in Vietnam numbered 3,000 by 1967. Most of these were in two army units, the Army Security Agency (ASA) and the Military Intelligence Corps. The work of military intelligence ranged from the signals intelligence of ASA, one of whose members became the first regular-army U.S. soldier to die in combat in 1961, to the electronic intelligence conducted by navy destroyers such as the ill-fated Maddox. In addition, military aircraft such as the SR-71 Blackbird and U-2 conducted extensive aerial reconnaissance.

As for CIA, by the time the war reached its height in the mid-to late 1960s, it had some 700 personnel in Vietnam. Many of these operated undercover groups that included the Office of the Special Assistant to the Ambassador (OSA, led by future CIA chief William Colby), which occupied a large portion of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

Cooperation and conflict. These three major arms of the intelligence and special operations war—Special Forces and other elite units, military intelligence, and CIA—often worked together. When Kennedy sent in the first contingent of Special Forces, they went to work alongside CIA, to whom the president in 1962 gave responsibility for paramilitary operations in Vietnam.

Unbeknownst to most Americans, CIA was also in charge of paramilitary operations in two countries where the United States was not officially engaged: Cambodia and Laos. Long before Nixon's campaign to cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail with strategic bombers, CIA operatives were training a clandestine army of tribesmen and mercenaries in Laos. Ordinary U.S. troops were not involved in this sideshow war in the interior of Southeast Asia: only Special Forces, who—in order to conceal their identity as American troops—bore neither U.S. markings nor U.S. weaponry.

CIA and army intelligence personnel worked on another notorious operation, Phoenix, an attempt to seek out and neutralize communist personnel in South Vietnam during the period from 1967 to 1971. CIA claimed to have killed, captured, or turned as many as 60,000 enemy agents and guerrillas in Phoenix, a project noted for the ruthlessness with which it was carried out. In this undertaking, CIA and the army had the nominal assistance of South Vietnamese intelligence, but due to an abiding U.S. mistrust of their putative allies, the Americans gave the Saigon little actual role in Phoenix.

The military and CIA debacles. In other situations, CIA and military groups did not so much intentionally collaborate as they found themselves thrown together, often at cross-purposes, or at least in ways that were not mutually beneficial. While U.S. Navy destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin were monitoring North Vietnamese electronic transmissions, CIA was busy striking at Viet Minh naval facilities with fast craft whose South Vietnamese (or otherwise non-American) crews made CIA involvement deniable. But North Vietnamese intelligence was as capable as its military, and they fired on the Maddox in direct response to this CIA operation.

The U.S. military became involved in another CIA debacle when, in 1968, army intelligence tried to resume a failed effort by CIA's Studies and Observation Group (SOG), another cover organization. From the early 1960s, SOG had been attempting to parachute South Vietnamese agents into North Vietnam, with the intention of using them as saboteurs and agents provocateur. The effort backfired, with most of the infiltrators dead, imprisoned, or used by the North Vietnamese as bait. CIA put a stop to the undertaking, but army intelligence tried to succeed where CIA had failed—only to lose several hundred more Vietnamese agents.

The U.S. Air Force had to take over another unsuccessful CIA operation, Black Shield, which involved a series of reconnaissance flights by A-12 Oxcart spy planes over North Vietnam in 1967 and 1968. Using the A-12, which could reach speeds of Mach 3.1 (2,300 m.p.h. or 3,700 k.p.h.), Black Shield gathered extensive information on Soviet-built surface-to-air missile (SAM) installations in the North. To obtain the best possible photographic intelligence, the Oxcarts had to fly relatively low and slow, and in the fall of 1967 North Vietnamese SAMs hit—but did not down—an A-71. In 1968, the U.S. Air Force, operating SR-71 Blackbirds, replaced CIA.

Assessing CIA in Vietnam. Despite the notorious nature of Phoenix or the CIA undertakings in Cambodia and Laos, as well as the occasions when CIA overplayed its hand or placed the military in the position of cleaning up one of its failed operations, CIA involvement in Vietnam was far from an unbroken record of failure. One success was Air America. The latter, a proprietary airline chartered in 1949, supplied the secret war in the interior, and also undertook a number of other operations in Vietnam and other countries in Asia. That Air America was only disbanded in 1981, long after the war ended, illustrates its effectiveness.

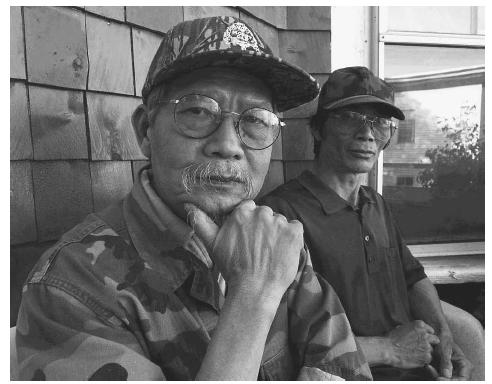

The popular image of CIA operatives in Vietnam as fiends blinded by hatred of communism—an image bolstered by Hollywood—is as lacking in historical accuracy as it is in depth of characterization. Like other Americans involved in Vietnam, members of CIA began with the belief that they could and would save a vulnerable nation from Soviet-style totalitarianism and provide its people with an opportunity to develop democratic institutions, establish prosperity, and find peace. Much more quickly than their counterparts in the military and political communities, however, members of the intelligence community came to recognize the fallacies on which their undertaking was based.

Intelligence vs. the military and the politicians. Whereas many political and military leaders adhered to standard interpretations about the North Vietnamese, such as the idea that they were puppets of Moscow whose power depended entirely on force, CIA operatives with closer contact to actual Vietnamese sources recognized the appeal of the Viet Minh nationalist message. And because CIA recognized the strength of the enemy, their estimate of America's ability to win the war—particularly as the troop buildup began in the mid-1960s—became less and less optimistic.

CIA appraisal of the situation tended to be far less sanguine than that of General Westmoreland and other military leaders, and certainly less so than that of President Johnson and other political leaders far removed from the conflict. In 1965, for instance, CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) produced a joint study in which they predicted that the bombing campaign would do little to soften North Vietnam. This was not a position favored by Washington, however, so it received little attention.

Whereas Washington favored an air campaign, General Westmoreland maintained that the war would be won by ground forces. Both government and military leaders agreed on one approach: the use of statistics as a benchmark of success or failure. In terms of the number of bombs dropped, cities hit, or Viet Cong and NVA killed, American forces seemed to be winning. Yet for every guerrilla killed, the enemy seemed to produce two or three more in his place, and every village bombed seemed only to increase enemy resistance.

The lessons of Vietnam. In the end, the United States effort in Vietnam was undone by the singularity of aims possessed by its enemies in the North; the instability and unreliability of its allies in the South, combined with American refusal to give the South Vietnamese a greater role in their own war; and a divergence of aims on the part of American leaders.

For example, the Tet Offensive, which resulted in so many Viet Cong deaths that the guerrilla force was essentially eliminated, and NVA regulars took the place of the Viet Cong, is remembered as a victory for the North. And it was a victory in psychological, if not military, terms. The surprise, fear, and disappointment elicited by the Tet Offensive—combined with a rise of political dissent within the United States—punctured America's will to wage the war, and marked the beginning of the end of American participation in Vietnam.

For some time, U.S. college campuses had seen small protests against the war, but in 1968 the number of these demonstrations grew dramatically, as did the ranks of participants. Nor were youth the only Americans now opposing the war in large numbers: increasingly, other sectors of society—including influential figures in the media, politics, the arts, and even the sciences—began to make their opposition known. In the final years of Vietnam, there was a secondary war being fought in the United States—a war concerning America's vision of itself and its role in the world.

By war's end, Vietnam itself had largely been forgotten. Despite earlier promises of a liberal democratic government, the unified socialist republic fell prey to the exigencies typical of communist dictatorship: mass imprisonments and executions, forced redistribution of land, and the banning of political opposition. Forgotten, too, were Laos and even Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge launched a campaign of genocide that killed an estimated two million people.

The Vietnamese invasion in 1979 probably saved thousands of Cambodian lives, but in the aftermath, Vietnam came to be regarded as a colonialist power. The nation once admired by the third world for standing up to America now became a pariah, supported only by Moscow—which had gained access to a valuable warm-water port at Cam Ranh Bay—and its allies in Eastern Europe.

During the remainder of the 1970s, America was in retreat, its attention turned away from the fate of countries that fell to communism or, in the case of Iran, to Islamic fundamentalist dictatorship. Americans focused their anger on those they regarded as having led them astray during the war years: politicians, the military, and CIA, which came under intense scrutiny during the 1975–76 Church committee hearings in the U.S. Senate. Only in the 1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, did the United States return to an activist stance globally.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Allen, George W. None So Blind: A Personal Account of the Intelligence Failure in Vietnam. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001.

Conboy, Kenneth K., and Dale Andradé. Spies and Commandos: How America Lost the Secret War in North Vietnam. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Kissinger, Henry. Years of Renewal. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Shultz, Richard G. The Secret War against Hanoi: Kennedy's and Johnson's Use of Spies, Saboteurs, and Covert Warriors in North Vietnam. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

Sorley, Lewis. A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America's Last Years in Vietnam. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

Wirtz, James J. The Tet Offensive: Intelligence Failure in War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

ELECTRONIC:

Vietnam War Declassification Project. Gerald R. Ford Library and Museum. < http://www.ford.utexas.edu/library/exhibits/vietnam/ > (February 5, 2003).

SEE ALSO

CIA (United States Central Intelligence Agency)

Cold War (1950–1972)

Cold War (1972–1989): The Collapse of the Soviet Union

Johnson Administration (1963–1969), United States National

Security Policy

Kennedy Administration (1961–1963), United States National

Security Policy

Nixon Administration (1969–1974), United States National

Security Policy

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: