Sex-for-Secrets Scandal

█ DAVID TULLOCH

On December 14, 1986, a United States Marine who had been serving as an Embassy guard in Moscow and Vienna turned himself in to CIA officials. The Marine, Sergeant Clayton J. Lonetree, claimed that he had given classified information to a KGB agent with the codename "Uncle Sasha." Immediately, a government investigation was launched into the affair, as officials searched for evidence that Lonetree had not been working alone, or was just one of many Embassy guards who was successfully targeted by the Soviets.

Violetta and 'Uncle Sasha.' Lonetree, a Winnebago Indian from St. Paul, Minnesota, had been a model soldier. He enlisted at age eighteen in the Marine Corps, and later underwent the difficult, elite training of the Security Guard Battalion School, from which he graduated in 1984. Lonetree was then assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, and later to the Vienna Embassy. While everyday duty as an Embassy guard can be repetitive, it is a key position, and often includes access to sensitive material, such as keys to offices or safes.

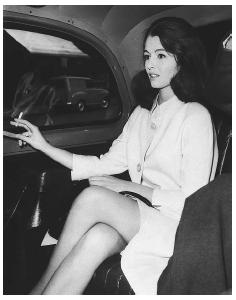

It was while stationed in Moscow that Lonetree met Violetta Sanni (sometimes given as Seina), a local Russian who worked as a translator, while attending the annual Marine ball held at the Ambassador's residence in November 1985. Lonetree began to date Violetta, despite the Marine Corps prohibition against guards having close contacts with Soviet citizens, and he seems to have fallen in love with her. Sanni then introduced Lonetree to "Uncle

Sasha," later identified as Alexi Yelsimov. At first Lonetree enjoyed the visits of Sasha, and they talked together about Lonetree's home, what his life had been like in the United States and on various political topics. However, Sasha was a KGB operative and he began to ask Lonetree questions.

Despite his concern, Lonetree continued to see Violetta and befriend Sasha, without notifying his superiors until the end of his Moscow tour. He was reassigned to the Vienna Embassy, where he was unexpectedly joined by Uncle Sasha. The KGB agent became Lonetree's only contact with Violetta, giving the lonely soldier photos and packages from Moscow, and passing on Lonetree's letters and gifts. Sasha used this new position as go-between to persuade Lonetree to provide documents and information from the embassy. Lonetree admitted to giving Sasha an old embassy phonebook and floor plans, for which he was paid $1,800. The Marine also provided details on suspected intelligence agents working undercover in the embassy.

Confession and conviction. Uncle Sasha began to demand more information from Lonetree, even suggesting a trip to Moscow for KGB training and to see Violetta again. Lonetree decided he had had enough, and turned himself in to the CIA. Nine months of intensive investigations began by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and other agencies, which led to an additional five other Marine guards being detained on suspicion of espionage, lying to investigators, and improper fraternization with foreign nationals.

One of these detainees was Corporal Arnold Bracy, who was also suspected of having a romantic liaison with a Soviet woman and being an accomplice of Lonetree's. Bracy signed a confession that stated he had helped commit a number of serious breaches of security. Bracy later claimed not to have read the document before signing it and to have signed under duress. A key claim in the confession was that Bracey and Lonetree had worked together to facilitate tours of the Moscow Embassy for KGB agents and allow them to plant listening devices. This allegation was denied by both Bracy and Lonetree, and it became evident that, working together, it would have been difficult for the two soldiers to show KGB agents through the embassy without being detected by other guards or electronic security measures. Eventually, all charges against Bracy were dropped. However, Lonetree was convicted on all of the thirteen charges he faced, becoming the first U.S. Marine to be found guilty of espionage.

Doubts surface. Lonetree was sentenced to 30 years in prison in November 1987 as well as a reduction in rank to private, the loss of all military pay and privileges, a $5000 dollar fine, and a dishonorable discharge. Even so, some doubts were raised about the NIS investigation, as a number of the accusations leveled against Lonetree, Bracy, and others were later shown to be unfounded.

In 1991, Lonetree returned to court asking that his conviction be overturned. In the U.S. Court of Military Appeals, lawyers claimed that Lonetree's confession had been inappropriately used as evidence against him, as it had been taken on the understanding that it would remain confidential. It was also suggested that Lonetree's lawyers at his original trial had been incompetent, as they had not informed their client of the possibility of a plea agreement. Additionally, they argued that Lonetree's cooperation should have earned him a drastically reduced sentence.

During Lonetree's trial, it was noted that one witness had remained anonymous, which was a violation of the defendants basic right "to know the identity of the witness against him." The witness, a CIA agent, had mostly testified in closed session. As well, military courts have procedures that differ from civil courts. At one time, it was even claimed that Lonetree had purposefully only given the KGB non-vital information, as he was planning to become a double agent.

While Lonetree's thirty-year sentence was not overturned, the court did agree that it should be reduced. In May 1988 the term had been shortened by five years for the cooperation he had shown investigators. Then in October 1992 another five years reduction was given. After the unsuccessful appeal, yet another shortening of five years' was granted in July 1994. In 1996, after serving just under nine years in jail, Lonetree was released early for good behavior.

The material that Lonetree passed to the KGB was not considered of great significance, and one report suggested the security implications were probably minimal. However, by coming forward, Lonetree revealed significant security lapses within the embassy staff structure that sparked changes in procedures and improved security in embassies across the world.

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Barker, Rodney. Dancing with the Devil: Sex, Espionage, and the U.S. Marines—The Clayton Lonetree Story. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Headley, Lake, and William Hoffmann. The Court Martial of Clayton Lonetree. New York: Henry Holt, 1989.

Kessler, Ronald. Moscow Station: How the KGB Penetrated the American Embassy. New York: Scribner's, 1989.

SEE ALSO

Cold War (1972–1989): The Collapse of the Soviet Union

Navy Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS)

Reagan Administration (1981–1989), United States National

Security Policy