Watergate

█ ADRIENNE WILMOTH LERNER

Five men, known as the "White House plumbers," broke into the Watergate apartment and office complex on June 17, 1972. The well-trained burglars' mission was to raid Democratic Party offices in the complex and obtain secret documents pertaining to the presidential election. The five men, Frank Sturgis, Bernard Baker, Eugenio Martinez, Virgilio Gonzalez, and James McCord were caught and arrested. Subsequent investigations revealed the involvement of E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy in planning the break-in, and possible connections to the White House and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Three of the "White House plumbers," Liddy, McCord, and Hunt were former members of the CIA. When investigations revealed that the burglars used sophisticated eavesdropping and espionage equipment, the scandal grew to encompass the United States intelligence community. Eavesdropping devices, including wiretaps and tape recorders, were planted in the target Watergate offices before the break-in to monitor communications. During the burglary, the men used miniature cameras, complex lock

picks, and military issue walkie-talkies. Authorities discovered small canisters of tear gas on two of the men. Some of the tools were even marked with government identification numbers, evidence that the operation was planned or authorized by a member of the government. The White House, and President Richard Nixon himself, were soon implicated, elevating the Watergate incident to full-fledged political scandal at the highest political level.

The men involved in the Watergate affair were members of the Committee to Re-elect the President sometimes referred to colloquially as "CREEP." Months before the break-in, members of CREEP advised President Nixon to develop "political intelligence capabilities" to further his campaign. Facing public backlash from the war in Vietnam, Nixon's committee sought to discredit Democratic opponents in an attempt to gain ground in the election. Following the Watergate burglary, and the arrest of the "White House plumbers," Federal authorities conducted a full investigation of the incident. The White House, and CREEP, attempted to block full disclosure of the scandal.

The cover-up of the Watergate affair was itself a deft intelligence maneuver. Members of CREEP destroyed pertinent documents and encouraged allies in the United States intelligence community to do the same. The Nixon White House destroyed tape archives of phone conversations. FBI Acting Director Patrick Gray later resigned his post after admitting to destroying Watergate documents at the request of CREEP officials. Those in custody gave a series of false statements, committing perjury, in an attempt to distance the scandal from the Nixon administration. As a result, only three of the original eight men arrested were indicted. For a while, the cover-up was successful.

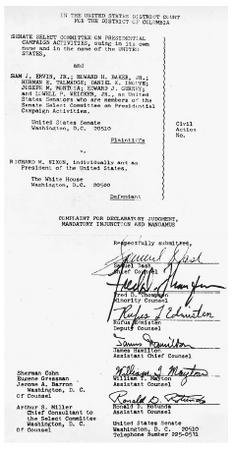

Following Nixon's re-election, the U.S. Senate began a formal inquiry of the Watergate scandal. The previous CIA and FBI investigations failed to implicate the Office of the President because none of the persons questioned mentioned the involvement of the White House in CREEP operations. In March 1973, Hunt asked for a significant sun of "hush money" to refrain from going to the FBI or Senate committee with information about the scandal. He received $75,000.

Most of those involved in the scandal decided to exercise their Fifth Amendment rights and not testify to the Senate committee. Nixon announced a new investigation of the scandal on March 21, 1973, but immediately began to stonewall the process. A letter from McCord to Judge Sirica on March 23 formally implicated the White House plumbers, CREEP, and the president in the Watergate scandal. The cover-up fell apart, and a desperate administration resorted to a series of "dirty tricks" to shift the focus of the investigation away from the Nixon administration.

The "dirty tricks" focused on discrediting those who testified against CREEP, White House, and intelligence agencies. Some were accused of sexual misconduct, others of financial irregularities. Stink bombs were planted in offices. However, the most devious trick was the falsification of State Department cables by Hunt to implicate former President John Kennedy in the assassination of the South Vietnamese President Diem. Hunt tried to sell the cables to the media, in an attempt to anger and influence predominantly Democratic Catholic voters. The timely surfacing of the mysterious cables, as well as public disclosure of campaign finance irregularities by the Nixon administration further fueled the scandal.

While the break-in itself was an illegal act, the Watergate scandal had far greater legal consequences. The involvement of former CIA members raised questions about the prevalence of political espionage in the United States government. Using the resources of the intelligence for political espionage or personal gain is strictly illegal under American law. In addition, the involvement of the White House implied the Office of the President resorted to gross abuses of its power and authority. Subsequent Senate hearings and FBI investigations reached similar conclusions, and nearly 30 people in the Nixon administration were fined or imprisoned.

Complex intelligence operations and sophisticated equipment had permitted the "White House plumbers," CREEP, and Nixon to perpetrate and hide many of their crimes. However, the same sophistication of cloak and dagger operations ultimately undid the Nixon administration and broke the mysteries of the Watergate scandal. Nixon recorded most conversations in his office. An intense legal battle, eventually reaching the Supreme Court, ensued over the tapes, their possible editing, and their admissibility in Senate Select Committee hearings. Facing impeachment after the subpoena of the tapes, Nixon resigned his office. Although he was later pardoned by President Gerald Ford, some of the people involved in the scandal served long prison terms, never breaking their cover story in relation to the scandal.

The most important political scandal in U.S. history was perhaps best put in perspective by the late comedian Bob Hope, who said of Watergate, "It gave dirty politics a bad name."

█ FURTHER READING:

BOOKS:

Bernstein, Carl, and Bob Woodward. All the President's Men, 25th Anniversary Edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999.

Kurland, Philip B. Watergate and the Constitution (The William R. Kenan, Jr., Inagural Lectures). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Kutler, Stanley I. The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1992.

ELECTRONIC:

United States National Archives and Records Administration. Watergate resources. < http://www.archives.gov/digital_classroom/lessons/watergate_and_constitu ion/teaching_activities.html >(01 December 2002).

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: